Collection of AMC Amsterdam.

Collection of AMC Amsterdam. 2.2-5aH ~18 cm | For having said to a guard, “I feel sorry for people who do not understand art”

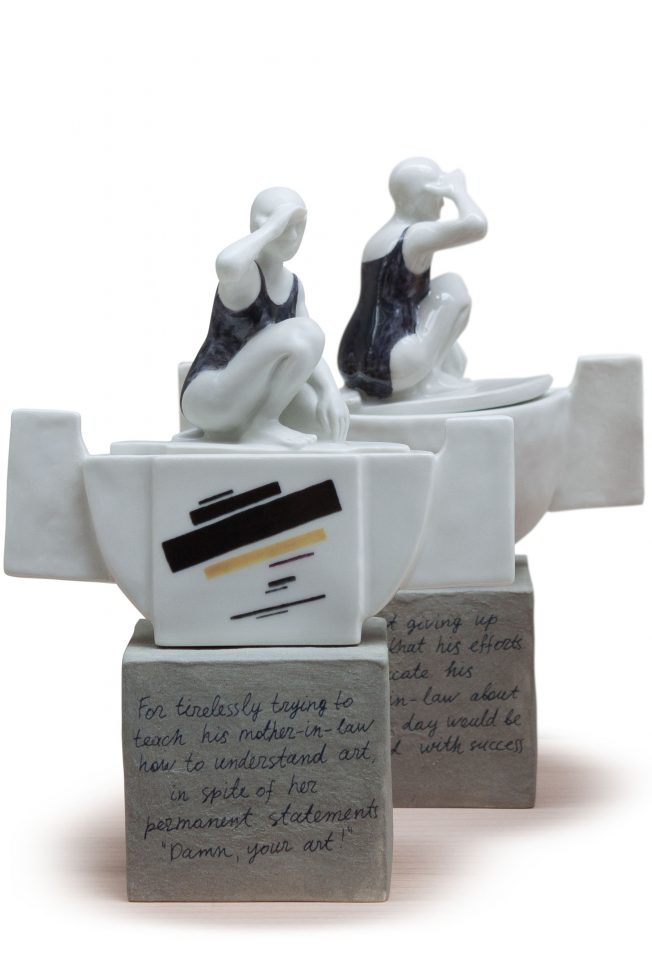

2.2-5aH ~18 cm | For having said to a guard, “I feel sorry for people who do not understand art” 2.2-4abH ~21 cm | For tirelessly trying to teach his mother-in-law how to understand art, in spite of her permanent statements "Damn, your art!" || H ~21 cm | For not giving up the hope that his efforts to educate his mother-in-law about art one day would be crowned with success

2.2-4abH ~21 cm | For tirelessly trying to teach his mother-in-law how to understand art, in spite of her permanent statements "Damn, your art!" || H ~21 cm | For not giving up the hope that his efforts to educate his mother-in-law about art one day would be crowned with success 2.2-3aH ~32 cm | For discussing the concept of metamorphosis in the paintings of the artist V.T. with the members of a medical board during an annual health survey

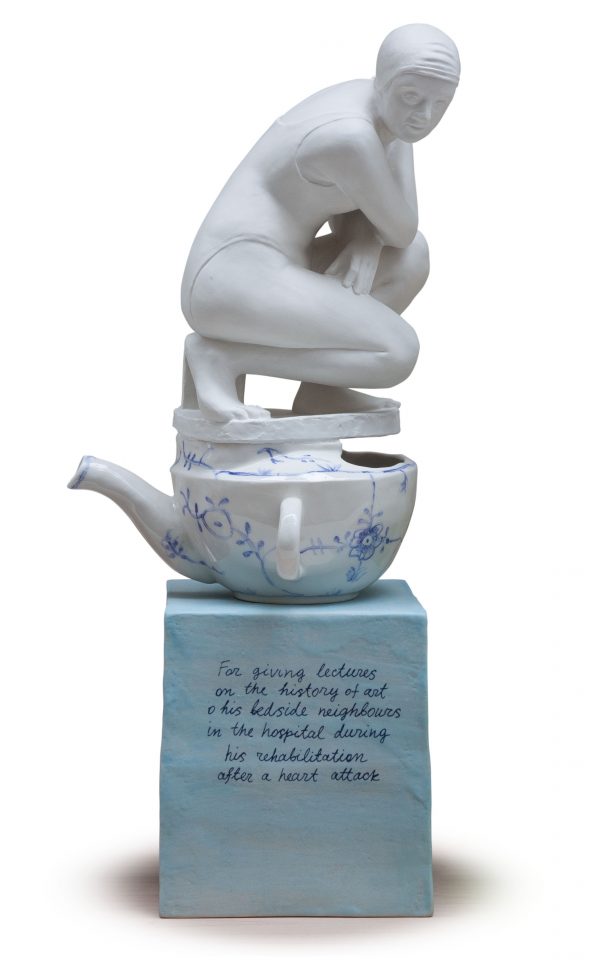

2.2-3aH ~32 cm | For discussing the concept of metamorphosis in the paintings of the artist V.T. with the members of a medical board during an annual health survey 2.2-2aH ~36 cm | For giving lectures on the history of art to his bedside neighbours in the hospital during his rehabilitation after a heart attack

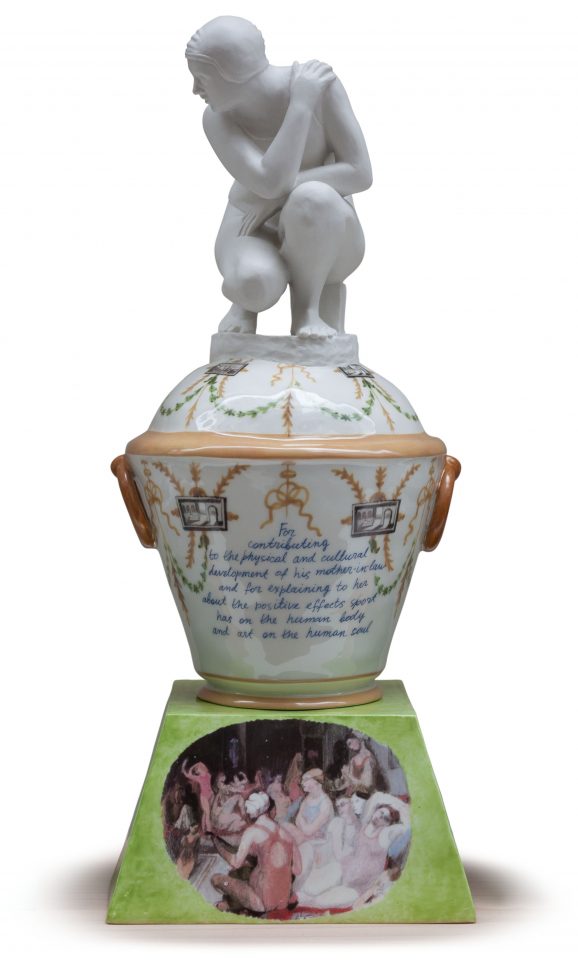

2.2-2aH ~36 cm | For giving lectures on the history of art to his bedside neighbours in the hospital during his rehabilitation after a heart attack 2.2-1H ~46 cm | For contributing to the physical and cultural development of his mother-in-law and for explaining to her about the positive effects sport has on the human body and art on the human soul

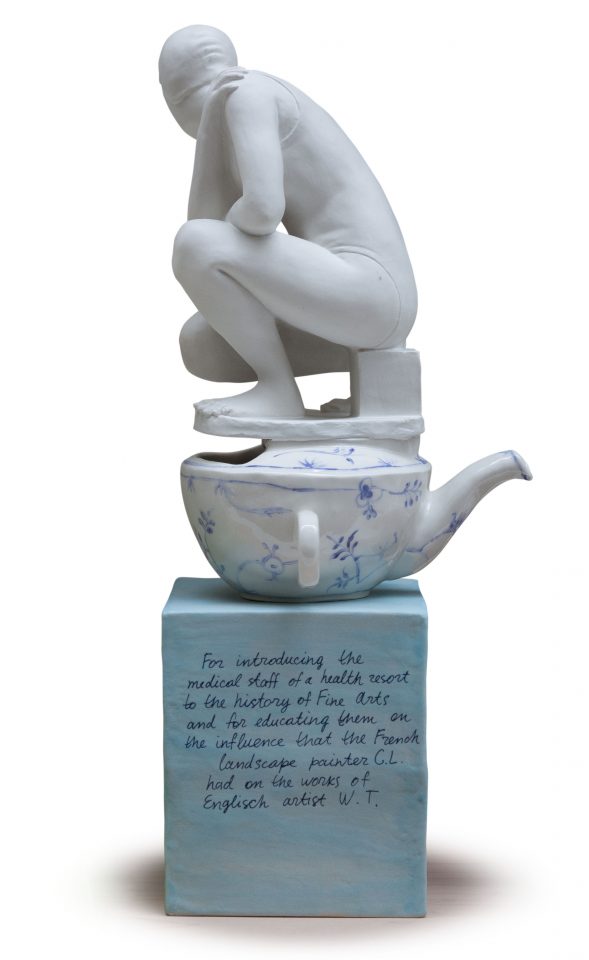

2.2-1H ~46 cm | For contributing to the physical and cultural development of his mother-in-law and for explaining to her about the positive effects sport has on the human body and art on the human soul 2.2-2bH ~36 cm | For introducing the medical staff of a health resort to the history of Fine Arts and for elucidating them on the influence that the French landscape painter C.L. had on the works of English artist W.T.

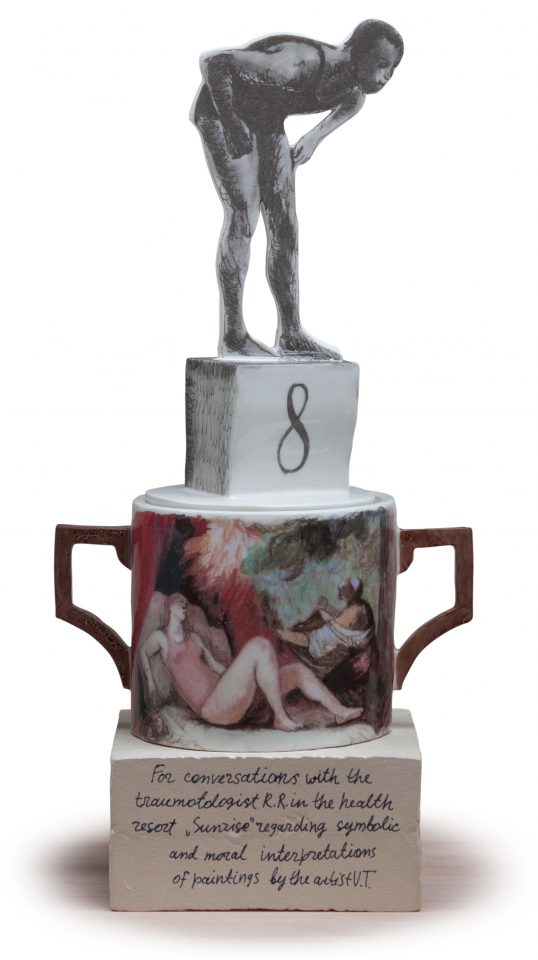

2.2-2bH ~36 cm | For introducing the medical staff of a health resort to the history of Fine Arts and for elucidating them on the influence that the French landscape painter C.L. had on the works of English artist W.T. 2.2-3bH ~32 cm | For conversations with the traumatologist R.R. in the health resort “Sunrise” regarding various symbolic and moral interpretations of paintings by the artist V.T.

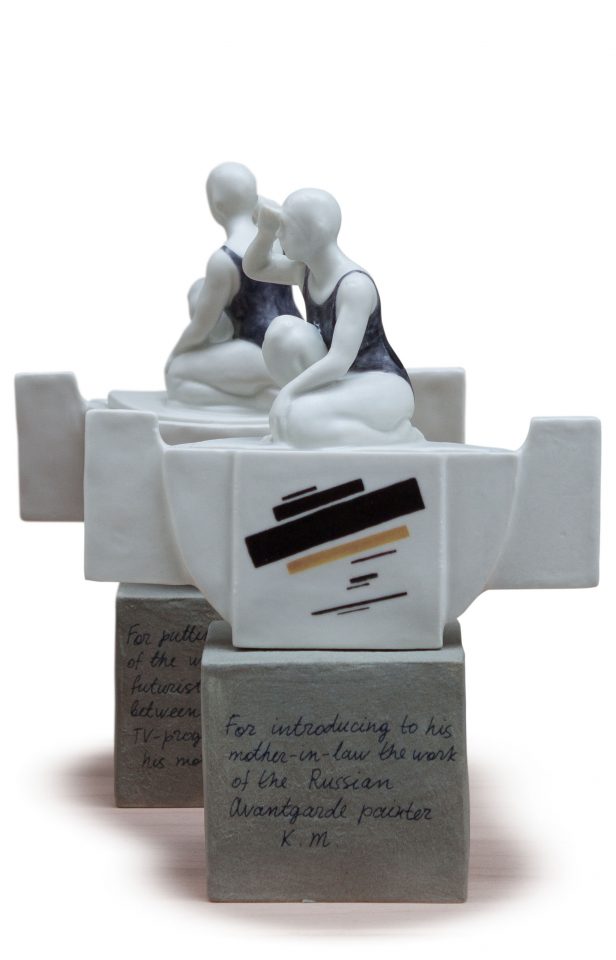

2.2-3bH ~32 cm | For conversations with the traumatologist R.R. in the health resort “Sunrise” regarding various symbolic and moral interpretations of paintings by the artist V.T. 2.2-4cdH ~21 cm | For putting reproductions of the works from the futurist movement between the pages of a TV-program read by his mother-in-law || H ~21 cm | For introducing to his mother-in-law the work of the Russian Avantgarde painter K.M.

2.2-4cdH ~21 cm | For putting reproductions of the works from the futurist movement between the pages of a TV-program read by his mother-in-law || H ~21 cm | For introducing to his mother-in-law the work of the Russian Avantgarde painter K.M. 2.2-5bH ~18 cm | For saying to his neighbours in a health resort, “Beauty heals”

2.2-5bH ~18 cm | For saying to his neighbours in a health resort, “Beauty heals”-

The Trophy Cups,

or What Could have Happened to My Father.Since my childhood I have already known that one of the biggest misfortunes, which could happen to a person, is to live with the feeling, that you have not realized your talent and just wasted your life. I even remember that chill coming over my heart that this can happen to me as well. I do not know why, but I could hardly imagine anything worse than that.

My father was a swimming coach. He was born in a small village. When he was a child he went regularly to a local river to swim and to exercise, trying to find out his own swimming technique and to improve his results. In other words, he had a vocation to become a coach. I have to smile every time when I try to imagine how my father was coaching himself as a child.

Almost 30 years ago my father was one of the best coaches in the Soviet national swim- ming team. He was very innovative and devoted to his work; he had his own vision of coaching methods. It was extremely important to him to have a success, to get better results, to win. The swimming pool was his second home. After working with him his swim- mers essentially improved their results. That time was a heyday of his career. He was invited to move from provincial Minsk to Leningrad or to Moscow. He was also invited to work as a coach in the USA and Canada; sport magazines were publishing articles about his coaching methods. He told me that at least ten of his swimmers were on their way to Olym- pic medals.

But then some circumstances started to hinder his career. My mother did not want to move to Leningrad or to Moscow. To move abroad was also impossible to my father, because the family could not go with him. Also his straight character and his intransigence to an incom- petence of the sport functionaries had a consequence that he was slowly removed from the leading position. Even to the Olympic games in Canada, where his swimmer won a medal, my father went not as a coach, but as a tourist, watching his victory from stands as an ordi- nary sideliner. For many years his best and most promising swimmers were taken away from him and transferred to other coaches. At a certain moment he became very frustrated and decided to leave the professional sport, feeling totally unrealized and underestimated as a coach. He could prepare many champions, but instead he had to finish his career as an ordinary sport teacher at the University in Minsk.

I always felt that my father had a lot regrets and unrealized ambitions. These days he is devoted to some other than sport matters. He became an art admirer and started to collect paintings. He often goes to the village, where he was born and grown up. He likes to walk there in the places, where he trained himself as a child. And I think he is very happy, because now he sees everything around him with the different eyes, as an artist. I also think, that he always was an artist.

At that time, when he left his job as a coach, he probably thought, that his life was over. But in fact, talent and ambitions can be realized in some other ways and forms than we think, and these ways can make us even happier. As my grandmother would have say about my father’s sport career: "Plague take it!"

So now, in this work, I also try to reflect on, what is at the end a "realization"? Could it take different forms? Maybe the most important thing is not a professional success, but rather that, what is left in shadow, is much more important and valuable?

Supported by the Mondriaan Fonds and The Frozen Fountain.

-